Of the four medieval parish churches that once existed on the High Street only two now remain: St Stephen's and St Petrock's left. The Church of Allhallows was demolished for road-widening in 1906 and St Lawrence's was badly damaged in 1942 and later removed.

Of the four medieval parish churches that once existed on the High Street only two now remain: St Stephen's and St Petrock's left. The Church of Allhallows was demolished for road-widening in 1906 and St Lawrence's was badly damaged in 1942 and later removed.Legend states that St Petroc was the son of a Welsh king who travelled from Ireland to Cornwall in the mid-6th century, settling first in Petrocstow (modern-day Padstow) before founding a monastery at Bodmin. After travelling from Brittany to Rome, St Petroc passed through Devon, where up to seventeen churches dedicated to him still survive. St Petrock's in Exeter is one of them. Like Exeter's other churches dedicated to a Celtic saint (e.g. St Kerrian's in North Street), the foundation of St Petrock's is ancient. Perhaps St Petroc himself was responsible. Exeter in the 6th century was just emerging from the ruins of its Roman past and was slowly transforming into what would become an important Anglo-Saxon centre and it's certainly possible that St Petroc himself stopped at 'Caerwisc' on his journey through Devon. The little guide to the church issued by the Diocese of Exeter states that St Petrock's is "possibly as ancient a church foundation as any in the city". It possibly even predates the foundation of the former monastery at St Mary Major in the 7th century.

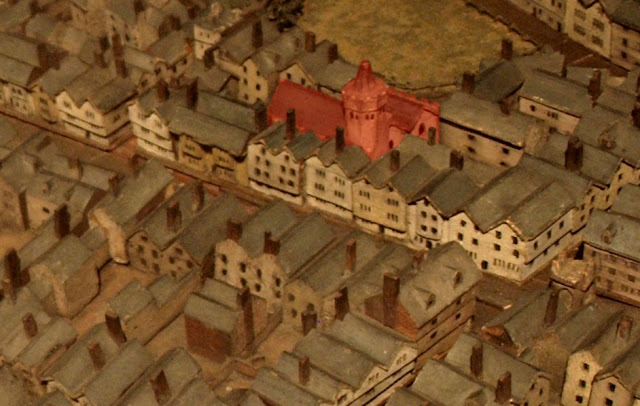

The 1587 map of the city right shows the tower of St Petrock's highlighted in red, peeping out from the houses that fronted onto South Street. The church is labelled "St Peroks". The great pinnacled medieval water conduit that once stood almost in the centre of the Carfoix is visible to the left. Also visible are the churches of St George, St Olave and Allhallows.

The 1587 map of the city right shows the tower of St Petrock's highlighted in red, peeping out from the houses that fronted onto South Street. The church is labelled "St Peroks". The great pinnacled medieval water conduit that once stood almost in the centre of the Carfoix is visible to the left. Also visible are the churches of St George, St Olave and Allhallows.No physical traces of the Celtic church remain today, but despite Cresswell's claim that structural alterations have "stripped [the building] of all architectural merit" the existing church still retains some interest beyond the historical importance of its early beginnings. Nothing is known of the very early phases of the church building. The Anglo-Saxon structure itself probably went through various stages and alterations. No doubt it was altered again after the Norman Conquest of 1066 and it was specifically mentioned in a mandate by Bishop Marshall in 1191 and again by Peter de Palerna in his Deed of Assignment of c1200.

The location of the church alone indicates its former significance, standing almost in the very centre of the city, at the junction of Exeter's four most important streets (High Street, North Street, South Street and Fore Street (or perhaps Smythen Street). The crossroads at which these four thoroughfares met became known in the Middle Ages as the Carfoix or Carfax, itself derived from the French quatre voix meaning the 'four ways'. Its position within the city meant that St Petrock's medieval and Tudor congregation consisted of many wealthy merchants and civic officials, despite the relatively small size of its parish.

The most important development for St Petrock's in the 13th century was the apparent rerouting of the High Street. Until 1286 the main East-West route through Exeter is thought to have run from the West Gate, up Smythen Street and then on up the High Street to the East Gate. It's difficult to imagine now but St Petrock's is believed to have stood to the north of the High Street and not to the south as it does today. The church was essentially on the other side of the road.

The most important development for St Petrock's in the 13th century was the apparent rerouting of the High Street. Until 1286 the main East-West route through Exeter is thought to have run from the West Gate, up Smythen Street and then on up the High Street to the East Gate. It's difficult to imagine now but St Petrock's is believed to have stood to the north of the High Street and not to the south as it does today. The church was essentially on the other side of the road.The aerial view left shows the pre-13th century footprint of St Petrock's highlighted in purple, much smaller than the church which exists today. Exeter's four main roads are highlighted in red. The course of the High Street as it perhaps existed before 1286 is highlighted in yellow. The reason behind the alteration to the street plan was the murder of the Cathedral's precentor, Walter Lechlade in November 1283. Following a visit to the city by Edward I and Eleanor of Castile in 1285, the cathedral authorities received permission to enclose the entire cathedral precinct within a wall, punctuated at regular intervals by gatehouses. It was decided that the south wall of St Petrock's itself would provide one stretch of the precinct wall. The High Street was therefore shoved northwards so as not to impede the movement of traffic, an alignment which remains to this day.

The existence of doors in both the north and south walls meant that the church building acted as a kind of postern gatehouse in its own right, allowing people to access the Cathedral Yard from the High Street. The church was originally founded on a standard east-west alignment and by the 14th century consisted of a simple chancel and nave with a bell tower at the western end.

The existence of doors in both the north and south walls meant that the church building acted as a kind of postern gatehouse in its own right, allowing people to access the Cathedral Yard from the High Street. The church was originally founded on a standard east-west alignment and by the 14th century consisted of a simple chancel and nave with a bell tower at the western end.The lower courses of St Petrock's north wall (shown in the photo at the top of this post) date from either the 12th or 13th century. The original height of the 14th century building extended as far as the string course running beneath the clerestory windows. These three windows, with limestone tracery, were added in the 16th century when the roof of the nave and the tower were heightened. The octagonal turret on top of the tower was added in 1736.

The plan right shows the evolution of the building from the 14th century until 1881. Note the houses which crowded outside the north wall and the narrow passageway that originally gave access into the church itself. These properties were all removed in 1905.

The church was penned in on the north side by the rerouted High Street and at its east and west ends by other properties, so the only room for expansion was towards the south. A new south aisle had already been built in 1413. A second, larger south aisle was added in 1513, named the Jesus Aisle, and this is probably also when the present tower, minus its octagonal belfry, was built. So extensive were the early-16th century alterations that the church was rededicated by Thomas Chard, the last abbot of Ford Abbey, who stood in for the ailing Bishop Oldham. Yet another south aisle was added in 1587.

The photo left shows part of the interior of St Petrock's today, looking west towards the tower. The tall, slender pillar to the right supports one corner of the tower itself. The gothic arches to the left, now blocked by modern partitioning, mark the original south wall of the medieval building before the first south aisle was constructed in 1413. The columns and angel capitals date from the additions made in the 16th century. St Petrock's was one of only four of Exeter many parish churches that was allowed to remain operational throughout the Commonwealth of the mid-17th century.

Jenkins paid it a visit in 1806 and left the following description: "the Church is an irregular building, which appears to have been erected at different periods, and is so obscurely situated and surrounded by houses, that scarce any part of it can be seen, except the Tower". Jenkins states that the tower held "a clock with a double-fronted dial, that projects over the houses" and which had "a set of chimes, which plays part of the 137th Psalm, at the hours of 4, 8 and 12". According to one source the clock was believed to date to 1470. This double-dialed clock no longer apparently exists.

The photo right shows the impressive capitals installed during the 16th century alterations. Carved angels each holding a shield, they represent a high level of decoration unusual in Exeter's surviving parish churches and are probably a reflection of the mercantile power of St Petrock's Tudor congregation. (It should be added that Pevsner said that these capitals "must date from 1828", although I don't understand the reasoning behind this claim. I see now reason not to think that they date to anything other than the 16th century.)

The photo right shows the impressive capitals installed during the 16th century alterations. Carved angels each holding a shield, they represent a high level of decoration unusual in Exeter's surviving parish churches and are probably a reflection of the mercantile power of St Petrock's Tudor congregation. (It should be added that Pevsner said that these capitals "must date from 1828", although I don't understand the reasoning behind this claim. I see now reason not to think that they date to anything other than the 16th century.)Jenkins's point about the church being surrounded by other buildings is interesting. The photo at the top of this post shows two blocked windows at street level in the north wall, so at some point the north wall must've been free of obstruction, the windows installed and then blocked at a later date with the erection of houses. The blocking of these windows probably explains why the nave was heightened in the 16th century and the clerestory windows inserted. These dwellings, referred to by Cresswell as "shabby little houses that huddled against the church", were subsequently demolished in 1905, revealing once again the north wall (and the blocked windows). The tablet on the wall of the tower states: "Obscured for two centuries, this church and tower were again brought into view by the widening of the High Street in the year of Grace 1905" above which are carved the heraldic arms of Exeter Cathedral and the arms of England. The poppy head ornamentation around the north door was also added at this time.

The photo left shows the 1881 chancel from Cathedral Yard with its five-light traceried window, the octagonal belfry visible in the background.

The photo left shows the 1881 chancel from Cathedral Yard with its five-light traceried window, the octagonal belfry visible in the background.In 1828-1829 yet more alterations were made when the south aisle of 1587 was enlarged to designs by Charles Hedgeland, the son of Caleb Hedgeland. The vaults were sealed over, new windows were let into the roof to improve the internal lighting, a new organ was installed and a new altar-piece was added to the chancel. Trewman's 'Exeter Flying Post' reported that the church had been "nearly rebuilt" when it opened its doors again on 15 November 1829.

And then in 1881 even more alterations were undertaken. By now the church had totally outgrown its 14th century form of a nave and chancel, and the almost endless extensions had created a church which was wider than it was long. The 1881 extension resulted in a drastic rearrangement of the church's interior. A new chancel was built to the south and the liturgical orientation of the church was turned through 90 degrees resulting in a north-south alignment with the altar at the south end. The old medieval chancel was converted into a baptistry.

These changes led the notable architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner to declare that the interior of St Petrock's was "among the most confusing of any church in the whole of England". The chancel was built on land purchased from the nearby Globe Inn (destroyed in 1942) and had an exposed pine roof, the chancel arch supported on small columns of Devonshire marble quarried from Ipplepen. A small lobby gave access into the Cathedral Yard and this is essentially how the church remains today.

St Petrock's contains a number of fine 17th and 18th century memorials, including the one shown right to William and Mary Hooper and which dates to the mid-1680s, the oldest being a tablet commemorating William Hurst, five times mayor of Exeter who died in 1568. William Hurst founded the almshouses which took his name outside of the East Gate and which eventually became the site of the Regency Devon and Exeter Subscription Rooms.

St Petrock's contains a number of fine 17th and 18th century memorials, including the one shown right to William and Mary Hooper and which dates to the mid-1680s, the oldest being a tablet commemorating William Hurst, five times mayor of Exeter who died in 1568. William Hurst founded the almshouses which took his name outside of the East Gate and which eventually became the site of the Regency Devon and Exeter Subscription Rooms.Also placed here is John Weston's 'Last Judgement' sculptural tablet which was relocated following the demolition of St Kerrian's in North Street in 1878, described by Pevsner as "a remarkable piece of carving". The belfry holds six bells, dating from the 15th to the 18th century and which are believed to be one of the lightest peals of six anywhere in Britain. The parish registers are some of the most complete in Devon too, surviving uninterrupted from 1538, the first year that Thomas Cromwell ordered that they be kept in every parish across England. The large collection of silver plate dates to between 1572 to 1692.

Not surprisingly, most of the historic buildings which once formed part of the parish of St Petrock's have been destroyed.

The image left shows a 1905 map of the city overlaid onto a modern aerial photo. Only those buildings that lay within the historical boundary of St Petrock's parish are highlighted. Buildings demolished since 1905 are highlighted in red, a consequence mainly of wartime damage in 1942 and, north of the High Street, post-war redevelopment for the Guildhall Shopping Centre. The only buildings in the parish that pre-date 1905 are highlighted in purple.

The most significant change in recent years has been the division of the church into two areas. The only area now open freely to the public is accessed via the north door in the High Street. A partition has recently been installed which divides the church roughly at a point where the original medieval south wall once stood, returning St Petrock's to something close to its medieval proportions. The rest of the building, including most of the 16th century and later alterations comprises the premises of a charity for the homeless, called 'St Petrock's'. It's worth visiting the accessible part of the church though, despite what Pevsner called its "peculiar secular character", as the interior is remarkably light and airy.

The photo below shows St Petrock's as it appears on Caleb Hedgeland's early 19th century model of Exeter. The High Street can be seen running in front of the church with properties obscuring its north wall. The passageway that led to the church's entrance was through one of the houses on the High Street.

Sources

No comments:

Post a Comment