Like Holy Trinity and St Mary Major, the medieval fabric of St Edmund's suffered from almost complete reconstruction during the 19th century. Apart from portions of the tower, the church in the photograph only dated to the 1833 but the origins of the church were much older. There is some uncertainty about the date of the first church. According to David Francis, the first church on the site "was probably a very small chapel taken down when the first stone Exe Bridge was built c.1200". Cresswell believed the chapel was late Saxon in origin. Unfortunately there's no archaeological evidence to support such an early structure. A 'chaplain of the bridge' is mentioned in 1196, soon after construction of the bridge had started, and it's possible that this chaplain was associated with St Edmund's.

A chapel on the bridge dedicated to St Edmund was definitely in existence by c1200 as it is mentioned in the will of Peter de Palerna. If there was an earlier structure on the site then it would've been demolished and rebuilt when the new bridge was built. The chapel of St Edmund didn't become a parish church until 1222.

A chapel on the bridge dedicated to St Edmund was definitely in existence by c1200 as it is mentioned in the will of Peter de Palerna. If there was an earlier structure on the site then it would've been demolished and rebuilt when the new bridge was built. The chapel of St Edmund didn't become a parish church until 1222.The image right shows a modern aerial view of the church overlaid onto which is the 1905 street plan of the city: remains of St Edmund's (1), the remains of the medieval Exe Bridge (2), the site of the lower leat (3), the site of the higher leat (4), the site of the West Gate (5), the original location of The House That Moved (6), the so-called 'Tudor House' in Tudor Street (7). The houses, factories and warehouses highlighted in red were demolished when the inner bypass was created in the 1960s and 1970s.

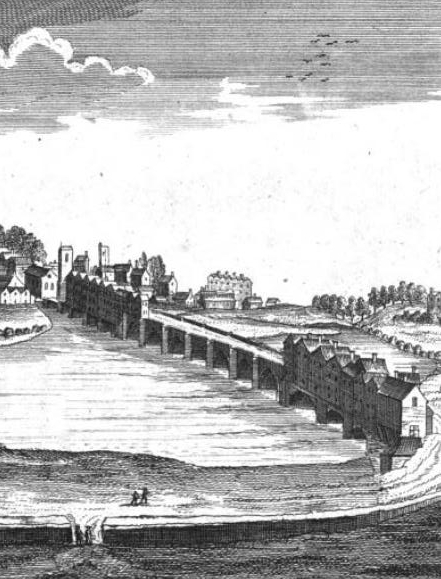

The great stone bridge that spanned the Exe, approximately 750ft long, was begun c1190 and probably took 40 or 50 years to complete. By the end of the 13th century there were three religious sites on it. A chantry chapel dedicated to St Mary, which stood opposite St Edmund's, and a chapel dedicated to St Thomas at the far (western) end of the bridge. St Edmund's stood at the eastern end, outside the city walls and close to the West Gate. It was built parallel with the bridge across two of the bridge's arches. The fabric of the church was supported underneath by stone pillars to allow water to pass underneath the church and through the spans of the bridge. (The place where the bridge started at its eastern end was more marsh than fast flowing river, at least for most of the year, the Exe being much wider and shallower then than it is today).

The drawing left shows St Edmund's Church in the 1830s before it was reconstructed. It looks like a normal street but it is in fact the carriageway of the medieval Exe Bridge with houses built on either side over the arches of the bridge. The two gabled houses next to the church tower are the street frontages of the two gabled houses that can be seen next to the church in the photograph at the top of this post.

The drawing left shows St Edmund's Church in the 1830s before it was reconstructed. It looks like a normal street but it is in fact the carriageway of the medieval Exe Bridge with houses built on either side over the arches of the bridge. The two gabled houses next to the church tower are the street frontages of the two gabled houses that can be seen next to the church in the photograph at the top of this post.The 13th century church was possibly a simple single-celled structure constructed from the same purple volcanic trap as the bridge itself. It underwent a series of alterations in the following centuries. The bell tower was added between 1448-1449 when Bishop Lacy was offering indulgences to anyone who would contribute towards the cost of a new belfry and a side aisle was added c1500. Fortunately a brief description of the late medieval church was made just after it had been almost completely demolished. The description appeared in an article in 'The Gentleman Magazine' in 1835: "The exterior, as far as could be seen, was built of red sandstone so common in the buildings of Exeter. The mullions and arches of the windows and doors, were executed in freestone, forming a pleasing variety. The doorcases and the two windows in the Church, with the lower one in the tower, are of the latter part of the fifteenth century. The square windows and door towards the east, are not earlier than the reign of Elizabeth. This portion of the structure may have been the residence of a chantry priest at a prior period. The interior consisted of a nave and side-aisle, divided by arches, either circular or very obscurely pointed, the columns octagonal, with moulded caps". The "red sandstone" was probably Heavitree breccia, a relatively poor quality stone used in Exeter from the 1350s onwards.

The drawing above was executed by the author of the article. It was, he said, "taken from an opposite window on 1st August 1830, at which time the demolition of the Church was talked about. A crack was visible in the north wall; but probably the fondness for improvement which has led to the rebuilding of several of the churches in the city, was the actual cause of its demolition. The protecting Genius of the Church would exclaim 'repair,' but 'not destroy;' but this small still voice would be drowned in the yells of the Demon of Improvement". It was ever thus.

Alexander Jenkins fills in a couple more details relating to the post-1833 church in his brief description of 1806: "The tower is small and not very lofty. It is crowned with a small spire and vane; it has six bells, which from their situation near the river have a very pleasing sound". Jenkins also mentions some remnants of painted glass in the windows that featured the heraldic shields of various Devon families.

Alexander Jenkins fills in a couple more details relating to the post-1833 church in his brief description of 1806: "The tower is small and not very lofty. It is crowned with a small spire and vane; it has six bells, which from their situation near the river have a very pleasing sound". Jenkins also mentions some remnants of painted glass in the windows that featured the heraldic shields of various Devon families.The photo right shows two of the remaining medieval pillars which once supported the floor of St Edmund's Church allowing water to flow under the church and through the bridge arch on the right.

The church was not only one of the four retained in Exeter during the Commonwealth that followed the English Civil War but it might've been the location for the city's first printing press. A printing press is known to have existed at Tavistock Abbey prior to the Reformation. After the abbey was dissolved in 1539 the press disappears. But in a will of 1567 the rector of St Edmund's, John Williams, cites "all such stuff as tooles concerning my printing with the matrice with the rest of the tooles concerning my press". It's probable that the rector was related in some way to William Williams, a known monk at Tavistock Abbey and that the press mentioned in 1567 was once at Tavistock Abbey.

On the morning of 19 August 1800 there was a tremendous thunderstorm over the city that raged for five or six hours. The church was struck by lightning, much to the excitement of the population. The "dial of the clock was beaten to pieces, the machinery of the chimes was deranged, the wire attached to it melted or burnt to small pieces, and scare any part of the church escaped injury". The sulphurous atmosphere left in the church after the strike made it difficult for the sexton to remain long in the building. The lightning conductor attached to the weathervane was blamed for carrying the lightning into the church itself.

By 1830 the church's future was in doubt. A report in the 'Exeter Flying Post' on 25 February announced that divine service had been suspended because of the "insecure state of St Edmund's Church".

By 1830 the church's future was in doubt. A report in the 'Exeter Flying Post' on 25 February announced that divine service had been suspended because of the "insecure state of St Edmund's Church".A meeting of the parishioners had been called by the rector "to consider the best means for reinstating it by a new edifice". On Thursday 06 September 1832 the 'Post' claimed that "the demolition of the Church of St Edmund on the Bridge in this city...was commenced on Monday morning". The same paper announced on 25 July 1833 that "We notice with much satisfaction the progress towards a finish of the New Church of St Edmund's on the Bridge - to that part of our city it will be a great ornament". If only.

Beatrix Cresswell in her 1908 book on Exeter's parish churches stated that "the present building had the misfortune to be erected in 1833, therefore, as a building, there is nothing more to be said for it". Perhaps that's a little unkind. I think the almost contemporary rebuilding of Holy Trinity resulted in a much poorer structure. At least the rebuilt St Edmund's above left had the look of Exeter's other remaining medieval parish churches, even if it had been stripped of nearly all of its historical fabric.

The postcard view above shows St Edmund's Church as it appeared at the beginning of the 20th century looking towards the city (the tower of St Mary Steps can just be seen amongst the rooftops in the background). The cityscape here remained little changed until the 1960s. With the creation of the new Exe Bridge in the 1770s part of the medieval bridge continued to be used as Edmund Street. The bridge was widened in 1854. The work involved in widening it can be seen in the stonework at the bottom of the photograph. This was all removed when the bridge was excavated in the 1960s, returning the structure back to its medieval form.

The aerial photograph below from c1930 shows part of the West Quarter and the leats of Exe Island. The Custom House is bottom right. St Edmund's Church is highlighted in red. Almost none of the buildings shown now survive. Many were swept away as part of slum clearances in the 1930s but the majority were demolished in the 1960s and 1970s during the creation of the inner bypass. The area today is completely unrecognisable. Similar devastation occurred outside the South Gate.

The new church was designed by the local architects of Cornish & Julian (Robert Cornish was also responsible for the Holy Trinity rebuild). A lot of the medieval material was recycled into the rebuilt structure. According to Cresswell, the tower was "in some measure retained, the top repaired with an ornamental parapet". The galleries that extended down the sides of the old church were replaced with a single gallery at the west end. The old painted glass mentioned by Jenkins was gathered into the windows of the north wall.

According to Cresswell the old font had been left in a stone mason's yard and the one in the church was modern i.e. from the 1830s. The pulpit was fashioned from the 15th century remains of its predecessor. Cresswell also claimed that some "old and rather uncomfortable looking open benches" had been brought from the cathedral at the time of the restoration i.e. in the 1870s.

According to Cresswell the old font had been left in a stone mason's yard and the one in the church was modern i.e. from the 1830s. The pulpit was fashioned from the 15th century remains of its predecessor. Cresswell also claimed that some "old and rather uncomfortable looking open benches" had been brought from the cathedral at the time of the restoration i.e. in the 1870s.There were eight bells in the tower which, said Cresswell, "had a very pleasant tone". The old church had three bells in 1533 and five when it was demolished in 1832. The oldest bell that Cresswell saw was dated 1721 with four others dated 1731. Three others dated to 1833 and were installed when the church was rebuilt.

In 1881 the issue of how much of the medieval tower had been left standing resulted in some bickering between the rector of St Edmund's and the city council. In that year the late 17th century houses shown adjacent to the church tower in the photograph at the top of this post were demolished by the city council as part of a slum clearance. The rector wanted to know why the council wasn't prepared to pay for the repairs necessary to the wall of the tower where the house nearest to the tower once stood. He cited a precedent. In 1879 the city council had demolished No. 210 High Street, an early 17th century house that was next to Allhallows Church in Goldsmith Street, and had paid for repairs on the church's newly-exposed wall.

But the council were having none of it and informed the rector that "whereas in the case of Allhallows the house was built against the church, in St Edmund's the church was built against the house". The rector responded with a letter from the churchwardens which stated that "it was obvious that the original wall of the old church was not disturbed when the present church was built (some fifty years since) from the fact that the walls of the old houses still adhered to the west end, the reason doubtless being that to remove the wall would endanger the safety of the premises". The churchwardens also complained that two large beams that had supported the timber-framed houses had been left in the west wall of the church. The churchwardens were undoubtedly correct but it appears that the parishioners ended up paying for the repair work themselves.

But the council were having none of it and informed the rector that "whereas in the case of Allhallows the house was built against the church, in St Edmund's the church was built against the house". The rector responded with a letter from the churchwardens which stated that "it was obvious that the original wall of the old church was not disturbed when the present church was built (some fifty years since) from the fact that the walls of the old houses still adhered to the west end, the reason doubtless being that to remove the wall would endanger the safety of the premises". The churchwardens also complained that two large beams that had supported the timber-framed houses had been left in the west wall of the church. The churchwardens were undoubtedly correct but it appears that the parishioners ended up paying for the repair work themselves. The photograph above left shows the surviving west wall of the tower that was at the centre of the disagreement in 1881. Constructed largely from red Heavitree breccia with some random blocks of purple volcanic trap, it is almost certainly a surviving fragment from the medieval church of St Edmund. The remaining part of the tower's south wall, shown above right with the entrance doorway, dates to the rebuilding of 1833. The photo below shows the Edwardian Exe Bridge c1910 looking towards New Bridge Street and the city centre. New Bridge Street was created at the end of the 18th century and bypassed the route into Exeter from the west along the medieval Exe Bridge. The isolated tower of St Edmund's Church is visible to the right.

The church probably started to go downhill after the Georgian Exe Bridge was opened in the 1770s, although Jenkins claimed in 1806 that "the whole of the decorations and furniture in this small edifice is kept in perfect repair". It was effectively sidelined as New Bridge Street made for a much easier entry into the city from the west, and St Edmund's was always one of Exeter's smaller medieval parishes even before the new bridge was built. The church was last used for regular services in 1956 and was then partially damaged by fire in 1969. Although the damage wasn't irreparable, the construction of the inner bypass and the consequent demolition of almost every surrounding building resulted in St Edmund's own demolition in 1973 after nearly 800 years of use as a site of worship. What was believed to be the surviving portions of the medieval building were retained and left as a 'picturesque' ruin along with the remains of the old Exe Bridge now "incongruously sited on a roundabout" (Pevsner & Cherry).

Sources