The remains of the medieval bridge that once spanned the river Exe at Exeter is one of the earliest structures of its kind in England above. Eight and a half arches out of a likely total of 17 or 18 still survive today, although the ninth arch is mostly buried under the modern ring road. Along with the cathedral, castle and the city walls, the medieval Exe Bridge is one of Exeter's major monuments of the Middle Ages. It's likely that there was a wooden Roman bridge spanning the river at the important civitas of Isca Dumnoniorum. It's now believed that Roman influence extended much further west of Exeter than had previously been thought. Excavations in 2011 at Ipplepen, 16 miles west of Exeter, revealed a previously unknown large Romano-British settlement made up of roundhouses and the remains of a Roman road. This settlement was populated by the native Britons who probably traded with the newly-arrived Romans following the establishment of the fortress at Exeter c55 AD. At least one Roman road left Exeter to the west: a section of the modern A380 towards Newton Abbot is based on a known Roman route and there is some evidence of Roman tin-mining in Cornwall.

The remains of the medieval bridge that once spanned the river Exe at Exeter is one of the earliest structures of its kind in England above. Eight and a half arches out of a likely total of 17 or 18 still survive today, although the ninth arch is mostly buried under the modern ring road. Along with the cathedral, castle and the city walls, the medieval Exe Bridge is one of Exeter's major monuments of the Middle Ages. It's likely that there was a wooden Roman bridge spanning the river at the important civitas of Isca Dumnoniorum. It's now believed that Roman influence extended much further west of Exeter than had previously been thought. Excavations in 2011 at Ipplepen, 16 miles west of Exeter, revealed a previously unknown large Romano-British settlement made up of roundhouses and the remains of a Roman road. This settlement was populated by the native Britons who probably traded with the newly-arrived Romans following the establishment of the fortress at Exeter c55 AD. At least one Roman road left Exeter to the west: a section of the modern A380 towards Newton Abbot is based on a known Roman route and there is some evidence of Roman tin-mining in Cornwall.Anyway, work on the medieval stone bridge was probably in progress by 1190, although the first documentary reference to it is in 1196. John Hooker, writing in the mid 16th century, believed that this stone bridge replaced an earlier pedestrian bridge made of wood: "there was no stone bridge over the river of Exe, but only certain clappers of timber which served for men to pass over on foot". Hooker goes on to describe the perils associated with trying to cross the river: "in the winter the passage was very dangerous and thereby many people perished and were carried away with the floods and drowned".

The river at Exeter has changed so much over the last thousand years that it's difficult to imagine what it was like in the 12th century but it was once much wider and much shallower than it is today with marshes on either side. It was also a tidal river and at certain times of the day in summer the decreased flow of the water would've exposed glistening mudflats. (The effect of the tides on the river at Exeter were largely eliminated following the building of the Countess Weir of 1296.) The dangers described by Hooker probably came from trying to ford the river in carts and on horseback as well as the frequent destruction of the wooden footbridge by violent winter floods. It was still possible to ford the river as late as the 17th century. A 1662 drawing of the medieval Exe Bridge by Willem Schellinks (illustrated in Hoskins' 'Two Thousand Years in Exeter') shows mounted figures picking their way through the water against a backdrop of the old stone bridge.

The difficulty in crossing the river was noticed by two of Exeter's citizens: Nicholas Gervase and his son, Walter. Despite their own personal wealth, the Gervase family were unable to fund the building of the bridge themselves. Instead Walter Gervase went on a tour of England collecting money for the project from anyone who was willing to donate while his father remained in Exeter to oversee the initial construction. Gradually the bridge was built, arch by arch, as finances allowed. According to Hooker, Walter Gervase raised £10,000, enough both to complete the bridge and to purchase land for its endowment. The aerial view above left shows the remains of the old bridge. The conjectural location of the now missing sections, based on a plan by John Steane, is highlighted in red. The medieval sites are numbered as follows: St Thomas's Church (1), St Edmund's Church (2), St Mary's Chantry Chapel (3), the West Gate (4), Stepcote Hill (5). The perimeter of the city wall is highlighted in purple.

The difficulty in crossing the river was noticed by two of Exeter's citizens: Nicholas Gervase and his son, Walter. Despite their own personal wealth, the Gervase family were unable to fund the building of the bridge themselves. Instead Walter Gervase went on a tour of England collecting money for the project from anyone who was willing to donate while his father remained in Exeter to oversee the initial construction. Gradually the bridge was built, arch by arch, as finances allowed. According to Hooker, Walter Gervase raised £10,000, enough both to complete the bridge and to purchase land for its endowment. The aerial view above left shows the remains of the old bridge. The conjectural location of the now missing sections, based on a plan by John Steane, is highlighted in red. The medieval sites are numbered as follows: St Thomas's Church (1), St Edmund's Church (2), St Mary's Chantry Chapel (3), the West Gate (4), Stepcote Hill (5). The perimeter of the city wall is highlighted in purple.The construction of the stone bridge probably took about 50 years to complete with work ending c1238. It was an enormous structure, approximately 750ft (229m) in length and must've been a wonder to everyone who saw it in the 13th century.

By the time it had been completed the bridge had three chapels. On the city side was the church of St Edmund and, almost opposite, a chantry chapel dedicated to St Mary. On the far side was a church dedicated to St Thomas. Nicholas Gervase, the father, died before the bridge was complete and he was reputedly buried in St Edmund's church. When Walter Gervase died in 1256 he was allegedly buried at the chantry on the bridge dedicated to St Mary. (According to George Oliver, when the chantry chapel was demolished in July 1833 the workmen discovered a tall skeleton under the floor which was then reinterred on the site.)

In reality both Nicholas Gervase and his son Walter were probably buried in the Cathedral Close, as stipulated in Walter's will of 1257. There were also two official positions connected with the bridge. One was the Chaplain of the Bridge, first mentioned in 1196. The chaplain probably officiated at St Edmund's church, which had been located near the eastern end of the bridge since at least 1214. The second was the Warden of the Bridge. The warden administered the various endowments of land and property associated with the bridge. His bronze seal matrix, bearing an impression of the bridge and the latin inscription 'S'Pontis Exe Civtatis Exoniae' ('Seal of the Exe Bridge of the City of Exeter'), still survives and is on display in the city museum, above right. A mid 13th century document is the earliest to survive still bearing a wax impression of the seal.

No-one knows exactly where the bridge started and finished, but on the city side at least it almost certainly began outside the West Gate, the main entrance into medieval Exeter from the west. Cowick Street, on the west side of the river, was on the same alignment as the medieval bridge (although this alignment is difficult to make out following the alterations to the street plan in the 18th and 20th centuries).

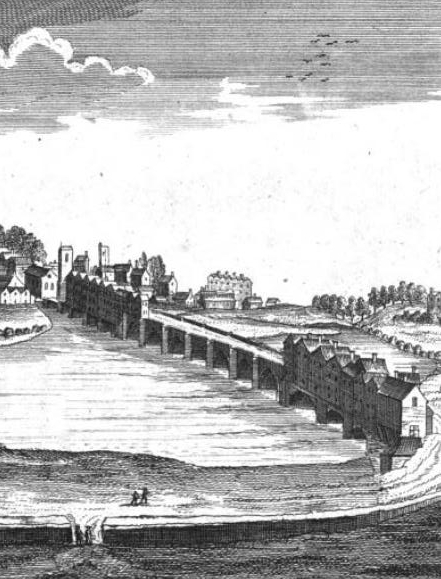

Anyone crossing the bridge after its completion would've passed through the West Gate and up Stepcote Hill into the city centre. Hogenberg's 1587 plan of the city, based on a drawing by John Hooker, shows the Exe Bridge in some detail, left. In reality the bridge had more arches than is shown but St Edmund's church is visible towards the West Gate, as is Frog Street. The plan also shows the recesses in the bridge used by pedestrians to keep out of the way of carts. Various mills and leats can also seen. The mills were used for fulling cloth, upon which much of Exeter's medieval and early post-medieval wealth was based.

The image below is a drawing of the medieval Exe Bridge by the early 19th century historian Alexander Jenkins. It shows the houses that were built on the arches at either end of the bridge. The six arches in the centre remained clear of buildings and never seem to have had any structures on them. The little turret on the right marks the bell tower of St Edmund's church. Jenkins' 1806 description of the bridge states that in the centre of the bridge "was a doorway, and a flight of steps, that led to a long vaulted room, commonly called the Pixhay, or Fairy House." There was also a weir made of wattle, visible in the foreground, which Jenkins said was designed to "prevent the fall of water from injuring the foundation". The Pixie House, built into the central cutwater, was probably a public latrine which emptied directly into the river.

There appear to have been efforts made to reclaim some of the swampy ground outside the city walls to the west just before or just after the bridge was completed. With the creation of the bridge, and limited space within the city walls, what was once waste ground would've suddenly gained economic importance. One example of this reclamation was Frog Street (now demolished) which ran between the West Gate and St Edmund's church. Archaeological excavations at Frog Street have recovered large bits of domestic pottery dated to c1230, contemporary with the construction of the bridge itself. This process of land reclamation was to continue throughout the Middle Ages resulting in the creation of the industrial area known as Exe Island. As more land was reclaimed the River Exe was gradually shunted into a narrower channel and eventually attained its present course.

There appear to have been efforts made to reclaim some of the swampy ground outside the city walls to the west just before or just after the bridge was completed. With the creation of the bridge, and limited space within the city walls, what was once waste ground would've suddenly gained economic importance. One example of this reclamation was Frog Street (now demolished) which ran between the West Gate and St Edmund's church. Archaeological excavations at Frog Street have recovered large bits of domestic pottery dated to c1230, contemporary with the construction of the bridge itself. This process of land reclamation was to continue throughout the Middle Ages resulting in the creation of the industrial area known as Exe Island. As more land was reclaimed the River Exe was gradually shunted into a narrower channel and eventually attained its present course.Almost from the moment of its construction the bridge was subjected to numerous floods. According to Jenkins, in 1286 "the summer proved very wet; which caused great inundations; a considerable part of Exe-Bridge was carried away by the high waters".

The bridge was repaired but was damaged again by floodwaters in 1384 that caused some loss of life. One of the casualties of the constant floods was the chapel dedicated to St Thomas that had been established at the western end of the bridge in the mid 13th century. In the early 1400s the chapel was almost entirely destroyed and the parishioners rebuilt the chapel further away from the river (this explains the location of what is now the parish church of St Thomas in Cowick Street. The rebuilt church was consecrated in 1412 but was badly damaged in 1645 during a battle between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians). Jenkins reported in 1806 that "according to tradition, the scite of the ancient chapel was in Ford's garden, near Gouldshay; the angle of a stone wall, with some foundations, were lately visible near the edge of the river".

By the middle of the 15th century the bridge was in a very poor condition. In 1447 John Shillingford, the mayor of Exeter, petitioned John Kemp, Archbishop of York and Lord Chancellor, for help with repairing the bridge. In 1539 one of the middle arches of the bridge collapsed and its repair was ordered by the warden, Edward Bridgeman, occupier of the former residence of Abbots of Tavistock in South Street.

Stone from the recently dissolved Priory of St Nicholas within the city walls was used for repairs so fulfilling a prophecy recounted by Hooker, that "the ryver of Exe should run under St. Nicholas Church". One of the stones perhaps taken from the priory at this time was the shaft of a late Anglo-Saxon cross carved from Dartmoor granite. It was found in front of one of the bridge's cutwaters when part of the bridge was demolished in 1775. An alternative location for the cross before it was reused in the fabric of the bridge was outside the West Gate. A 'broken cross' is mentioned in a city roll of 1316-1317. This is possibly Toisa's Cross, mentioned by Jenkins as having stood at the West Gate "but long since demolished". Either way, the cross shaft was retrieved from the waters and purchased by William Nation who placed it at the corner of his house at No. 229 High Street. In 1911 the 10th century shaft was moved to the grounds of the surviving priory buildings, above right, and in 1991 it was finally placed in the city's museum where it can still be seen today.

After 600 years the bridge was finally replaced in the 1770s. According to Jenkins, "the intricate, and inconvenient, entrance into the city over the Old Bridge (by which all carriages, and travellers, were obliged to enter at West Gate and, to avoid the steep ascent of Fore-street hill, proceed commonly by the way of Rock-lane) made an alteration absolutely necessary". The replacement of the bridge and its beautiful Georgian successor is covered here. Jenkins states that "as soon as the new bridge was completed, the greater part of the old one was taken down, as far as the houses at the Eastern end". The demolition left only the nine arches that still survive today but the bridge continued to be used as Edmund Street, "a great conveniency to such people as have occasion to go to the Southern parts of the city".

A detail from Benjamin Donn's 1765 map of Exeter above right shows the medieval bridge before it was replaced in the 1770s. Most of the structure is obscured by housing. The old houses that stood on the bridge are particularly interesting. It seems that nearly two-thirds of the bridge once had houses on it with only the central six arches being left free of structures. The medieval houses were deliberately destroyed during the English Civil War but they were replaced between 1650 and 1700.

The image left is an animation using stereoscopic photographs taken in the 1860s (.apng compatible browsers only). It shows surviving late 17th century timber-framed houses balanced on the arches of the medieval bridge. The tower of St Edmund's church is to the left. As far as I know it's the only photograph ever taken of these properties, although such was their peculiar, antique charm that they appeared in several drawings and watercolours throughout the 19th century (e.g. the houses on the south side of the bridge were sketched by JMW Turner in 1811). The water running beneath the two visible arches isn't the River Exe, which by 1880 was some distance away, but the leat of the nearby Cuckingstool Mill. The image shows the rear of four properties with galleries overhanging the water on the ground floor.

It seems incredible that these buildings could've been constructed on such a narrow structure (especially when it's remembered that similar properties would've been on the other side of the bridge with the narrow carriageway running between them). Part of the secret lay in timbers that sprang from the stone arches of the bridge to support a great horizontal beam. This beam supported the rear of the houses while allowing the water to flow through the arches unimpeded. The architect James Crocker believed this to be the "most picturesque peep to be found in the city of Exeter" and, had this small ensemble survived, I think it would've been among the most photographed scenes in Devon.

The illustration right shows the view down the carriageway of the medieval Exe Bridge towards St Thomas c1830. St Edmund's church, constructed over two of the bridge's arches, appears on the right prior to its reconstruction in 1833-34. By this date over half of the bridge had been demolished but the eastern half, closer to the city, had retained its ancient aspect and many of its timber-framed properties. As mentioned by Jenkins, the houses on the western end of the bridge were demolished in the 1770s, after the new bridge had been constructed. Most of the properties on the south side of the bridge were demolished when the remaining arches were widened in 1854 to improve Edmund Street. The houses on the north side of the remaining portion of the bridge survived well into the latter-half of the 19th century.

Members of the Royal Archaeological Insitute toured Exeter's historical buildings in 1873 and a report in the 'Exeter Flying Post' stated that "the remains of old Exe-Bridge attracted much attention. Many of the houses on the north side of the bridge remain and a few of the arches of those crossing some mill leats exist." The report goes on to say that "the interesting part were the houses...they saw the remains of a seventeenth century house built on the bridge".

Unfortunately the houses shown in the photograph, the last of their kind still standing, were demolished in 1880. To see something similar to the medieval Exe Bridge as it would've appeared in the 16th or 17th centuries you have to travel to the German city of Erfurt in Thuringia. The Krämerbrücke, part of which is shown above left, is the only surviving bridge in northern Europe to retain its timber-framed housing. The properties are constructed in a similar manner to the houses at Exeter, the backs jettied out over the edge of the bridge on huge wooden beams supported by timbers set into the stone arches.

Like the Exe Bridge, the Krämerbrücke also had a chapel at either end of the bridge. Although wider, the Krämerbrücke is a fraction of the original length of the medieval Exe Bridge, just 259ft (79m) in comparison with the Exe Bridge's 750ft (229m). The Krämerbrücke also has houses along its full length unlike the medieval Exe Bridge which had a gap in the housing over the six central spans.

By 1900 the only building of historical interest left on the bridge was St Edmund's church and that had been largely rebuilt in the 1830s. And the remnants of the bridge itself were largely forgotten, the remaining medieval arches buried beneath later road surfaces and the brick additions made when Edmund Street was widened in 1854.

By 1900 the only building of historical interest left on the bridge was St Edmund's church and that had been largely rebuilt in the 1830s. And the remnants of the bridge itself were largely forgotten, the remaining medieval arches buried beneath later road surfaces and the brick additions made when Edmund Street was widened in 1854.During the 1960s the entire area around the bridge was cleared to constuct part of the inner bypass. The surviving arches were evcavated and St Edmund's church was slighted so that it looked like a medieval ruin above right. Pevesner & Cherry's 'Devon' states incorrectly that the remains were "revealed by war damage". The bridge is now incongruously surrounded by a gyratory road system and I doubt it's visited as often as it should be.

So much for a brief summary of the bridge's history! This has already gone on forever, and I apologise to anyone still reading. I wanted to make these entries shorter but some mention should be made of the medieval engineering that went into the bridge. If only this was straight-forward but unfortunately it isn't. The shape of the arches is a mystery. Three of the remaining eight and a half have pointed arches while the rest have semicircular arches, more in keeping with a late 12th century date. The pointed and semicircular arches aren't even spaced out regularly but are mixed up seemingly at random. The obvious answer is that the pointed arches are of a later date but the evidence seems to suggest that the remaining eight and a half arches are all of the same build. Perhaps a different group of masons worked on the spans with the pointed arches but I'm not sure this is really believable either.

The pointed arches are also constructed differently to the semicircular arches. The spans with the pointed arches are constructed from five narrow ribs. The semicircular arches have just three much wider ribs, left.

The piers for the bridge were built on square stone foundations that rested on a bed of timber stakes. According to Jenkins, when the western end of the bridge was demolished in the 1770s the 600-year-old stone foundations were found to be resting on "an innumerable quantity of oak piles, driven thick into the ground. Some of these, on being drawn up, were very hard, and black as jet." Each of the piers had a cutwater on each side, a wedge-shaped structure of stone used to divide the current. Surrounding each cutwater there was probably a starling, a ring of piles driven into the riverbed and filled with gravel and rocks as a way of protecting the piers and cutwaters from flotsam carried on floodwater. These starlings would've made it look as though the bridge were floating on rafts. Little is left of most of the cutwaters although a couple do survive almost up to their full height.

The cutwaters on the south side were probably severely damaged when Edmund Street was widened in the mid 19th century. Although the cutwaters once provided a recess for pedestrians they must've been obscured when houses were constructed on the bridge. The cutwaters were all skewed in the direction of the current, quite an innovation at the time.

The bulk of the bridge was constructed from rubble with a facing of dressed blocks of purple volcanic trap quarried at various sites around Exeter. Unfortunately much of the dressed stone has disappeared, revealing the rubble core and giving the bridge a more ruinous appearance than it deserves, but the original exterior still survives in many places. The bridge also contains some sandstone and, most notably, blocks of white limestone. The limestone was used alternatively with the purple volcanic trap in the ribs of the pointed arches to create an attractive alternating pattern of colour, above right. One of the semicircular arches shows where the central rib collapsed and had to be repaired, probably in the 15th century, using inferior red Heavitree breccia.

The photograph below shows one of the pointed arches with the best of the surviving cutwaters. Much of the original dressed stonework is still intact on this section of the bridge. It's interesting to remember that this was the bridge that the rebels crossed during their assault of the city during the Prayerbook Rebellion of 1549, that the Royalists and Parliamentarians rode over during the English Civil War and that William of Orange crossed in 1688 on his journey from Brixham to London to be proclaimed King of England. It is now a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Sources

4 comments:

Thanks for the information

A very well researched and thorough description of Exon's 'inhabited' bridge and coupled with of all things actual 'photography' of it's properties and knowledge the houses were stiil in situ as late as 1880, remarkable!

Though I am sure you would have included it if you knew I have to ask, do you have any knowledge of the bridge inhabitants, were businesses carried out there for example?

I too 'found' Erfurt's 'Kramerbrucke', it encompasses a mid river island, but as you remark has no 'lookout' gaps, nor does it bridge a tidal river!

In England the tidal River Tyne was bridged from early times with a stone inhabited bridge, jointly maintained by the Sees of Newcastle[6 arches], Gateshead [4]. Several businesse were carried on eg. publishing and hardware. There was a drawbridge and three towers, including the Magazine Tower, sometimes used as a prison, each with portcullis!

On the 16th November 1771 after three days of heavy rain it, and eight other local bridges succumbed to a wild thunder storm. The tidal river beneath rose til it almost touched the arches, pillars were swept away, people were trapped and fell to their deaths in the boiling waters below, some bodies being found months later.

In 1781 it was rebuilt without houses! A 'copy' was erected for a Victorian Festival but I have only seen that drawn - no photographs - and almost nothing pictorially of the original, only distant drawings!

My interest is old London Bridge and it's community, and I contribute to:

www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/LondonBridge.htm

Absolutely fascinating, thankyou. I will look at the ruins in a different light next time.

You've honored this amazing structure and its history in a very thorough and interesting way! Wonderful!

Post a Comment